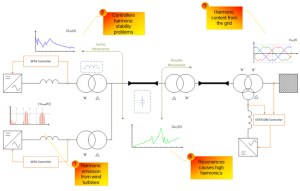

Let us think about various sources of harmonic problems in large wind power plants (WPPs) and different ways of optimized harmonic mitigation methods. We discussed previously about harmonic problems such as sources of harmonic emission and amplification as well as harmonic stability which are commonly seen in large WPPs. Fortunately a significant variety of modern preventive and remedial harmonic mitigation methods in terms of passive and active filtering are possible.

Passive filtering

Three-phase harmonic filters utilized in the WPPs nowadays are shunt elements. They are intended to decrease the voltage distortions at the point of interest. From the grid code requirements point of view, a WPP voltage distortion is evaluated at the point of common coupling (PCC).

Nonlinear elements such as the power electronic converters, transformers, etc. generate harmonic currents or harmonic voltages inside the WPP as well as in the external network. The resultant harmonic current flows throughout system impedance. Passive harmonic filters reduce distortion by providing low impedance to the harmonic currents.

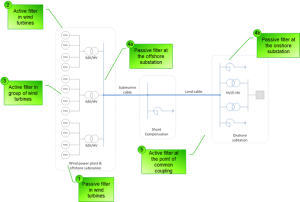

Typical shunt harmonic filters are presented in Fig. 1. Such filtering depending on the harmonic emission source can be installed either in the wind turbine circuit or somewhere at the WPP level (e.g. onshore substation, offshore substation, etc.).

Pros

- Known state-of-the-art technology,

- Relatively cheap solution,

- High reliability due to simplicity in the build,

- Effective if designed correctly.

Cons

- Significant size especially for lower frequencies (for large WPPs the tuned frequencies are getting lower),

- Additional losses,

- Can cause some over-voltages during switching operations (e.g. energization),

- Tuned only for specific frequencies (i.e. limited bandwidth),

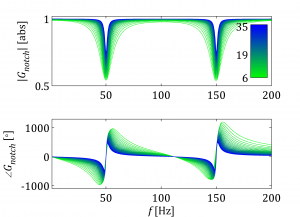

- Affected by uncertainties during the WPP design phase,

- Cannot be easily re-tuned in the case of changing grid conditions during the operation of the WPP,

- Uncertainties in terms of sizing due to lack of information from wind turbine manufacturers and TSOs during the design phase,

- Size limitations during design due to e.g. limited space at offshore substation,

- Long lead-time because of custom-made reactors.

Active filtering

All active filtering solutions employ power electronic converters for the absorption (e.g. harmonic compensation) or suppression (e.g. active damping) of harmonics. Nowadays large WPPs are already equipped with a number of grid connected converters either as a part of the wind turbines or as some sort of FACTS devices. In that case, the implementation of active filtering technique would only mean the retuning of the converter controller in order to meet with controlled harmonic levels.

The converter might be controlled adaptively or otherwise to suppress the selected critical harmonic components. From this perspective there is no need to interfere with the WPP design but it entails to providing additional control features. Such issues could be specified on a contractual level and required to be provided as an add-on together with the product.

Connecting all possible active filtering methods together with state-of-the-art passive filtering methods an optimized hybrid solution can be obtained.

Pros

- Already existing technologies such as STATCOMS can be utilized for the active filtering at the PCC,

- Active tuning might be permissible even during the operation,

- Almost unlimited control potential (e.g. selective harmonic compensation, wide band high-pass active filtering, etc.),

- Network impedance changes during operation could be addressed,

- Control method can be tuned for each of WPPs independently taking into consideration grid code issues as well as WPP structure,

- Negligible losses for series connected active filters such as wind turbines,

- Reduces risk due to uncertainties related with lack of information from manufacturers (e.g. models) and TSOs (e.g. harmonic background, models, etc.).

Cons

- Recent technology; not commonly applied in WPPs,

- May suffer from harmonic stability problems,

- Improved bandwidth and increased switching frequency is needed,

- Component sizing issues and limited DC-link voltage utilization.

[1] Ł. H. Kocewiak, "Harmonics in Large Offshore Wind Farms," PhD Thesis, Aalborg University, Aalborg, 2012.

[2] Ł. H. Kocewiak, S. K. Chaudhary, B. Hesselbæk, "Harmonic Mitigation Methods in Large Offshore Wind Power Plants," in Proc. of The 12th International Workshop on Large-Scale Integration of Wind Power into Power Systems as well as Transmission Networks for Offshore Wind Farms, Energynautics GmbH, London, UK, 22-24 October 2013, 443-448.